I find that the more I share my experiences of connecting with my ancestors and traveling to the places they once lived, the more questions I get about my process and approach to doing this work.

As a western woman who appreciates structure and likes to ask a lot of questions, I can really appreciate where that curiosity comes from.

And as I’m working to unlearn a lot of my patriarchal programming and embrace a more spiralic nature of being, I can see how a lot of my decolonization and ancestral connection process has been intuitive—an unfolding journey that leaves me little breadcrumbs to pick up and follow, from one to the next.

While telling you to follow the intuitive breadcrumbs and embrace the journey unfolding before you is part of my answer to this question of the how, I will do my best to share the more grounded, practical side of my experience in hopes it will help guide you on your journey of ancestral reconnection.

A few weeks ago, I published a post sharing my reasons and intentions for going on a pilgrimage to Maine—the place of my colonizer ancestry (where my ancestors first landed from Europe in the 1600s). Here’s how I figured out where to go and what to do:

I have the privilege of being able to access many genealogical records kept by my family, so Maine was a place I knew of—both by the stories of my mother and by the meticulously kept diaries and accounts culled by my great Uncle and the ancestry-obsessed folks that came before him.

There’s also much I don’t know about my ancestors.

The accounts I have access to were primarily written by the men and only include the stories they saw fit to include. I hear from a lot of folks mourning the loss of information and the lack of connection they have to their ancestors through historical records, which I can honor as a history nerd myself. However, I know in my bones that you can connect to your ancestors in so many ways—whether you have the actual written records or not. (Here’s a blog post with more about that)

I asked my mother about Maine after having several dreams about it.

I didn’t know where in Maine we were from, but I knew my ancestors first landed there when they came over from England and Ireland. As soon as I said Maine, my mother’s ancestral brain was activated and she blurted out the name of the island she used to spend summers in as a child (and where my aunt scattered the ashes of my grandmother).

Important Note: Because I am white and descended from European folks, I have a lot of privilege and access in genealogical research than people of color and native folks do. I highly recommend this podcast interview with Darla Antoine to learn more about this and anti-racist methods of doing your own research.

My role on this pilgrimage was to collect and keep the stories. My mother and aunt were the storytellers.

As we did our research and looked at maps, the stories began to come alive in them and we trusted each other to create a loose itinerary that would guide us on our pilgrimage. We had to put our FOMO (fear of missing out) aside and trust the path that was being laid before us.

I listened intently and certain names kept coming up—my great great Aunt Esther, a man named Royal, the patriarch of my mother’s father’s side, my grandmother, my great grandmother. I let my mother and aunt guide me and trusted my connection to these ancestors. If anything felt unsafe or not good, I would set those ancestors aside and follow the threads of the ones who felt good.

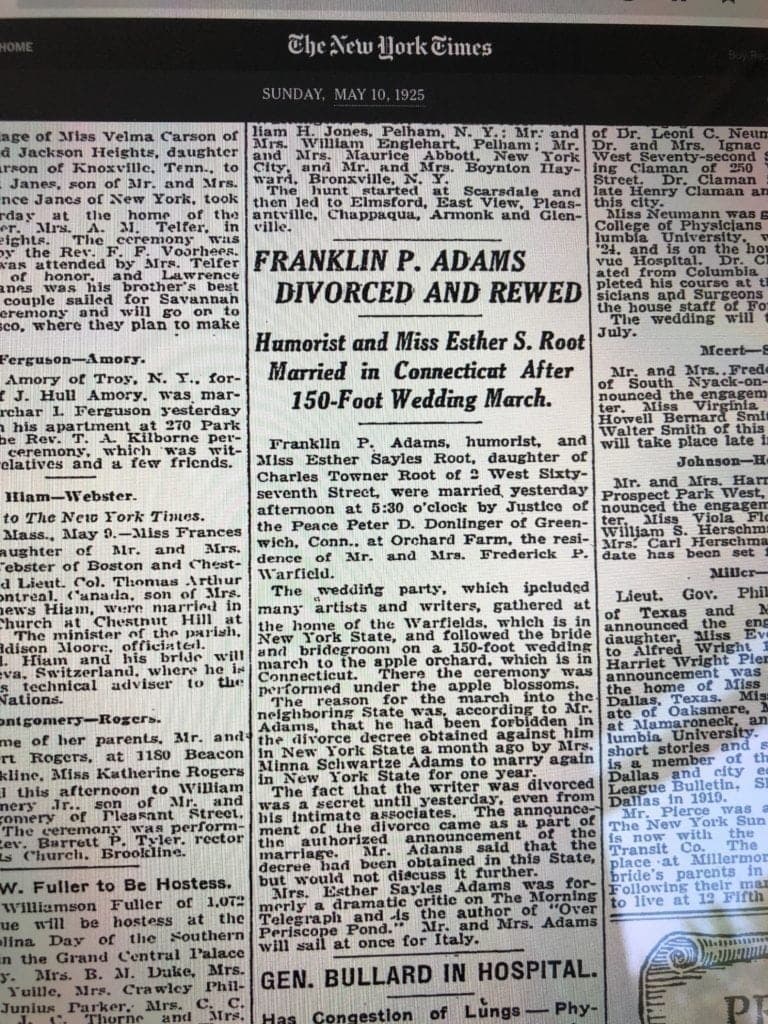

The scandalous wedding announcement of my great great Aunt Esther

I know not all of us know how to ask our parents and relatives about our ancestors.

And, if you add in any thoughts or beliefs in ancestral connection that aren’t a part of the dominant cultural narrative, we can feel super hesitant to begin these conversations.

I felt an open and curious mind from both my mom and aunt, but I definitely took a chance in sharing a vision I had during a meditation journey (that involved scrying with an apple core over a fire) where I met my maternal grandmother on an island of apple trees in England.

When I finished the story, I sucked in a breath wondering how they would react, and both of them said they had chills and were so honored I shared it with them. It was about 10 minutes later we all agreed to go to Maine together.

I have so many friends and clients tell me about asking their parents to talk to them about their ancestors (or even participating in rituals to honor them) and being surprised and delighted by their relatives’ response.

There is a hunger to reconnect to those who came before us.

There is a curiosity about the history of our people. There is a yearning to feel like we are a part of something ancient and codified throughout time. The conversations typically go better than you think.

It was very important to me that I include an act of reparations to the native ancestors of the land my ancestors colonized hundreds of years ago.

I went into this trip with very little information, but I knew what I needed to research: the specific areas my ancestors colonized and to which tribal nation that land belonged to.

I had enough information to know that my ancestors first landed in Boothbay, Maine and later built a home in Phippsburg. I took those locations and plugged them into the Native Land app to clearly see this was Abenaki territory—a grouping of smaller bands in the area and speakers of the Algonquin language.

I took some time to research both the history of the Abenaki people in Maine and figure out where they are today (the myth that indigenous folks aren’t still here today is what is known as the “Puritan Lie”).

I found out that the word Abenaki is derived from Wabanaki meaning “People of the Dawn Land”.

Before having contact with the European world, the Abenaki population was as high as 40,000. In the 1600s, when the Europeans arrived to Maine, over half their population died from sickness. A century later, fewer than 1,000 Abenaki remained after the Revolutionary War. They are a federally recognized tribe in Vermont and have around 2,500 members today.

After learning all of this information (and allowing myself to feel a range of emotions from guilt to grief knowing my ancestors played a major role in the near-decimation of these people), I started thinking about how I would make cultural reparations or amends to the people my ancestors had harmed.

I knew I wanted to give money to the Abenaki people, support any Abenaki artists I came across by purchasing their crafts, and do some sort of ritual on the land when I was there (trusting I would know what to do and when the time came).

I will go into more detail about what I did and how it went in my next post, but I hope this helped you think about ways you can approach a pilgrimage like this of your own.

Take what I’ve shared and find what will work for you.

Use what you have (ancestry.com, grandmother google, familysearch.com are also easy to access if you don’t have family records or stories) while also trusting what comes to you in a dream or a passing feeling. Allow yourself to feel any discomfort that comes up and challenge yourself to dig deeper when you find yourself wanting to run away from the research.

This work is powerful. This work is needed. This work is healing.

To engage in ancestral connection work and try to collect and remember those stories is to ground into a deeper purpose of who you are and why you are alive on this planet today. For those of us living on lands not originally belonging to our ancestors (which is 98% of us), it’s one thing to simply know about places our ancestors first landed upon migrating to their new world. It’s another to physically place your body on that land and courageously (and also responsibly) feel all that comes up from being there. This is the work that reconnects us to all that we are. This is the work of belonging.

Any other questions about my process?

Pop them in the comments below and I’ll be happy to answer.